Thursday, October 24, 2013

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

Battlefield Burials by Alann Schmidt

Battlefield

Burials After Antietam: A Most

Disagreeable Duty

Chief among the many long-lasting

impacts of the Battle of Antietam is the sheer enormity of tragedy and

loss. September 17, 1862 still

ranks as the most casualties in one day, in one place, in the history of the

United States of America – over 23,000 killed, wounded, and missing. Often overlooked is what happens after

the fighting ceases, as the glory of battle gives way to an unpleasant,

practical reality. In addition to

the medical care of thousands of wounded soldiers, the massive task of burying

thousands of the dead would have to be completed.

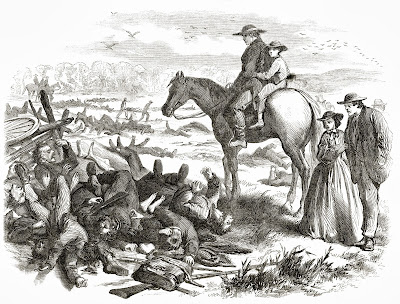

As the first field to be photographed

soon after the battle, images such as these show the horrific scope of the

fight. The Union army held the

field, so many in the ranks would need to be put into burial parties and

quickly get to work. Even so, it

would take days to complete such a grisly job.

“Our regiment has been detailed to bury

the dead, the most disagreeable duty that could have been assigned to us;

tongue cannot describe the horrible sights which we have witnessed. The Union soldiers were all buried when

we arrived on the field, the rebel dead lay unburied and hundreds still remain

so. I would not describe to you

the appearance of the dead even if I could, it is too revolting. You can imagine the condition of the

bodies when I tell you that they were slain on Wednesday and it is now

Sunday. I was up at the Provost

Marshall’s office this morning for permission to buy some liquor for our boys

to keep them from getting sick when at this disagreeable labor.”

--Lt. Origen Bingham, 137th PA

Some burials were individual graves,

but many were simply long trenches to hold multiple bodies. All those killed were buried, but obviously

the Union soldiers took care of their comrades first. Taken two days after the battle, most,

if not all, of the dead seen in photos would have been Confederates. Identification was often difficult, and

information on headboards and markings was mostly limited. There were even reports of grave

looting.

“Every man’s pocket was turned inside

out. Sometimes a piece of money, a

pocket knife, or something else would fall from the hands of the midnight

robbers, in the dark, and we would find it where they had turned the pocket,

but every one was robbed by the ghouls.

Well, we had the dead to bury, thousands of them… it was the most

disagreeable days work of my life.

First the grave had to be dug.

You Elkton folks saw the workmen dig for the water-works pipe – now add

a few thousand additional workmen, and extend the ditch about six miles, and

make it two or three feet wider and deeper. Now look in every direction and see hundreds carrying the

mangled bodies of those who had been shot.”

-J. Polk Racine, 5th MD

Obviously these were terribly

unpleasant conditions, and the warm weather lingered into late September. Contact with dead bodies would also be

a serious health hazard, as soldiers who came from all over the country brought

various diseases with them.

Disease killed many more soldiers than any battle, and the local

civilians were very susceptible as well.

No civilians were wounded or injured during the battle, but many died

from rampant disease in the weeks and months following. The full story of the many battle

impacts on the Sharpsburg area is best left for another complete blog entry,

but notable for our purposes is the simple fact that many of the farmer’s

fields became giant cemeteries, greatly impacting their agricultural operations

for years to come.

News of the battle quickly spread

across the country. Tourists came

to see the battlefield, and many family members came to care for and take their

loved ones back home.

Among the many who came to visit the

battlefield was a young wife whose frantic grief I can never forget. She came hurriedly as soon as she knew

her husband was in the battle only to find him dead and buried two days before

her arrival. Unwilling to believe

the facts strangers told her – how early in the morning they had laid him

beside his comrades in the orchard – she still insisted upon seeing him. Accompanying some friends to the spot

she could not wait the slow process of removing the body, and in her agonizing

grief clutched the earth by handfuls where it lay upon the quiet sleeper’s

form. And when at length the

slight covering was removed and the blanket thrown from off the face, she

needed but one glance to assure her it was all too true. Then passive and quiet beneath the

stern reality of this crushing sorrow she came back to the room in our house.

-Antietam Valley Record

Local man Aaron Good thankfully took

upon himself the task of identifying and documenting as many gravesites as he

could. This record became

essential in later planning for a proper cemetery, and he also was often

contracted to find the grave of a soldier and ship the body back home. The following letter, on display in the

Antietam Visitor Center museum, was sent to Good thanking him for his efforts.

New

York

85

W. 26th St.

4

June 1863

Mr.

Aaron Good

Dear

Sir,

We

received the remains of our son George Wilson (who fell at the Battle of

Antietam on Sept. 17th 1862) on last Friday evening at 6 o’clock,

but had got a letter in the morning notifying us of their coming. On their arrival we felt satisfied that

you had transacted your part of the contract faithfully and honorably, and

likewise felt happy to see that you had paid that respect to the remains of one

whom we had loved so dearly and had built our future hopes on more than we can

describe at present.

If

this communication can be of any service in inducing others to bring home the remains

of their relatives we consider it our duty to certify through this how we

appreciate your kindness in fulfilling your share of our most anxious hopes,

with the assurance that they may place all confidence in you and the

expeditious manner in which everything had been arranged to our entire

satisfaction.

George

& Margaret Wilson

As time passed, folks did their best to

get back to their normal daily routine, but in some ways the situation around

Sharpsburg did not improve. Most

of the burials were not quality work, not very deep, and even were sometimes

just dirt piled up on top of the ground.

It did not take long until heavy rainstorms and animals took their toll,

and exposed bones were a common sight.

Local citizens continued to contact their state representatives to try

to get something done, but it took until March 1864 for the Maryland General

Assembly to approve an act to establish an official soldier’s cemetery at

Sharpsburg. A board was appointed

and work soon got started to relocate the dead of the Battle of Antietam.

Finally the farmers of the area would

have their fields back, and more importantly, the men who sacrificed all for

their country would finally have a more appropriate, respectful resting place. The story of the battlefield burials

after the Battle of Antietam is an unpleasant, grisly, if not also fascinating

topic, but we must make sure that we remember that each one of the over 23,000

casualties was a person, and as one who paid the ultimate price in service to

their country, a person to be remembered and honored.

“Here

lie men who have not hesitated to seal and stamp their convictions with their

blood – men who have flung themselves into the great gulf of the unknown to

teach the world that there are truths dearer than life, wrongs and shames more

to be dreaded than death. And if

there be on earth one spot where the grass will grow greener than on another

when the next summer comes, where the leaves of autumn will drop more lightly

when they fall like benediction

upon a work completed and a promise fulfilled, it is these soldiers graves.”

New York Times, October 20, 1862

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)