For a short video showing what you can expect this Saturday, December 7, follow this link:

http://mms.nps.gov/ram/ncr/fqizrsl2.mov

Monday, December 2, 2013

Thursday, October 24, 2013

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

Battlefield Burials by Alann Schmidt

Battlefield

Burials After Antietam: A Most

Disagreeable Duty

Chief among the many long-lasting

impacts of the Battle of Antietam is the sheer enormity of tragedy and

loss. September 17, 1862 still

ranks as the most casualties in one day, in one place, in the history of the

United States of America – over 23,000 killed, wounded, and missing. Often overlooked is what happens after

the fighting ceases, as the glory of battle gives way to an unpleasant,

practical reality. In addition to

the medical care of thousands of wounded soldiers, the massive task of burying

thousands of the dead would have to be completed.

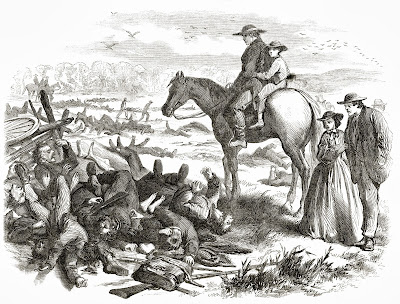

As the first field to be photographed

soon after the battle, images such as these show the horrific scope of the

fight. The Union army held the

field, so many in the ranks would need to be put into burial parties and

quickly get to work. Even so, it

would take days to complete such a grisly job.

“Our regiment has been detailed to bury

the dead, the most disagreeable duty that could have been assigned to us;

tongue cannot describe the horrible sights which we have witnessed. The Union soldiers were all buried when

we arrived on the field, the rebel dead lay unburied and hundreds still remain

so. I would not describe to you

the appearance of the dead even if I could, it is too revolting. You can imagine the condition of the

bodies when I tell you that they were slain on Wednesday and it is now

Sunday. I was up at the Provost

Marshall’s office this morning for permission to buy some liquor for our boys

to keep them from getting sick when at this disagreeable labor.”

--Lt. Origen Bingham, 137th PA

Some burials were individual graves,

but many were simply long trenches to hold multiple bodies. All those killed were buried, but obviously

the Union soldiers took care of their comrades first. Taken two days after the battle, most,

if not all, of the dead seen in photos would have been Confederates. Identification was often difficult, and

information on headboards and markings was mostly limited. There were even reports of grave

looting.

“Every man’s pocket was turned inside

out. Sometimes a piece of money, a

pocket knife, or something else would fall from the hands of the midnight

robbers, in the dark, and we would find it where they had turned the pocket,

but every one was robbed by the ghouls.

Well, we had the dead to bury, thousands of them… it was the most

disagreeable days work of my life.

First the grave had to be dug.

You Elkton folks saw the workmen dig for the water-works pipe – now add

a few thousand additional workmen, and extend the ditch about six miles, and

make it two or three feet wider and deeper. Now look in every direction and see hundreds carrying the

mangled bodies of those who had been shot.”

-J. Polk Racine, 5th MD

Obviously these were terribly

unpleasant conditions, and the warm weather lingered into late September. Contact with dead bodies would also be

a serious health hazard, as soldiers who came from all over the country brought

various diseases with them.

Disease killed many more soldiers than any battle, and the local

civilians were very susceptible as well.

No civilians were wounded or injured during the battle, but many died

from rampant disease in the weeks and months following. The full story of the many battle

impacts on the Sharpsburg area is best left for another complete blog entry,

but notable for our purposes is the simple fact that many of the farmer’s

fields became giant cemeteries, greatly impacting their agricultural operations

for years to come.

News of the battle quickly spread

across the country. Tourists came

to see the battlefield, and many family members came to care for and take their

loved ones back home.

Among the many who came to visit the

battlefield was a young wife whose frantic grief I can never forget. She came hurriedly as soon as she knew

her husband was in the battle only to find him dead and buried two days before

her arrival. Unwilling to believe

the facts strangers told her – how early in the morning they had laid him

beside his comrades in the orchard – she still insisted upon seeing him. Accompanying some friends to the spot

she could not wait the slow process of removing the body, and in her agonizing

grief clutched the earth by handfuls where it lay upon the quiet sleeper’s

form. And when at length the

slight covering was removed and the blanket thrown from off the face, she

needed but one glance to assure her it was all too true. Then passive and quiet beneath the

stern reality of this crushing sorrow she came back to the room in our house.

-Antietam Valley Record

Local man Aaron Good thankfully took

upon himself the task of identifying and documenting as many gravesites as he

could. This record became

essential in later planning for a proper cemetery, and he also was often

contracted to find the grave of a soldier and ship the body back home. The following letter, on display in the

Antietam Visitor Center museum, was sent to Good thanking him for his efforts.

New

York

85

W. 26th St.

4

June 1863

Mr.

Aaron Good

Dear

Sir,

We

received the remains of our son George Wilson (who fell at the Battle of

Antietam on Sept. 17th 1862) on last Friday evening at 6 o’clock,

but had got a letter in the morning notifying us of their coming. On their arrival we felt satisfied that

you had transacted your part of the contract faithfully and honorably, and

likewise felt happy to see that you had paid that respect to the remains of one

whom we had loved so dearly and had built our future hopes on more than we can

describe at present.

If

this communication can be of any service in inducing others to bring home the remains

of their relatives we consider it our duty to certify through this how we

appreciate your kindness in fulfilling your share of our most anxious hopes,

with the assurance that they may place all confidence in you and the

expeditious manner in which everything had been arranged to our entire

satisfaction.

George

& Margaret Wilson

As time passed, folks did their best to

get back to their normal daily routine, but in some ways the situation around

Sharpsburg did not improve. Most

of the burials were not quality work, not very deep, and even were sometimes

just dirt piled up on top of the ground.

It did not take long until heavy rainstorms and animals took their toll,

and exposed bones were a common sight.

Local citizens continued to contact their state representatives to try

to get something done, but it took until March 1864 for the Maryland General

Assembly to approve an act to establish an official soldier’s cemetery at

Sharpsburg. A board was appointed

and work soon got started to relocate the dead of the Battle of Antietam.

Finally the farmers of the area would

have their fields back, and more importantly, the men who sacrificed all for

their country would finally have a more appropriate, respectful resting place. The story of the battlefield burials

after the Battle of Antietam is an unpleasant, grisly, if not also fascinating

topic, but we must make sure that we remember that each one of the over 23,000

casualties was a person, and as one who paid the ultimate price in service to

their country, a person to be remembered and honored.

“Here

lie men who have not hesitated to seal and stamp their convictions with their

blood – men who have flung themselves into the great gulf of the unknown to

teach the world that there are truths dearer than life, wrongs and shames more

to be dreaded than death. And if

there be on earth one spot where the grass will grow greener than on another

when the next summer comes, where the leaves of autumn will drop more lightly

when they fall like benediction

upon a work completed and a promise fulfilled, it is these soldiers graves.”

New York Times, October 20, 1862

Sunday, September 22, 2013

Antietam: A Battle for Freedom

Antietam:

A Battle for Freedom

Daniel

J. Vermilya

Rarely in history has the link between

the blood shed on the battlefield and the freedom of millions been so clear. At

the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862 over 23,000 men fell as

casualties in a single day of battle—more battle casualties than had fallen in

America’s previous wars combined. Just five days later, on September 22, 1862,

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation at a

meeting of his cabinet. This preliminary document was the result of a long

struggle, going back to the very foundation of the country. From the moment

that Thomas Jefferson penned those immortal words, “all men are created equal,”

a great national debate spread through the nation, attempting to define

citizenship, personhood, and freedom. In 1861, that debate descended into war.

By the summer of 1862, with casualties mounting across the country, Lincoln

realized it was time to embrace a higher goal for the conflict. Something

needed to be done about the causes of the war. With thousands of Americans

dying on the field of battle, a decision needed to be made regarding the future

of slavery in the United States. On July 22, 1862, Lincoln held a cabinet

meeting, where he introduced a draft for a proclamation declaring that all

slaves in the states in rebellion would be freed under his powers as Commander

in Chief. While several of his cabinet members greeted the proclamation

favorably, Secretary of State William Seward suggested Lincoln wait for a Union

victory before issuing such an important document. Seward believed putting

forth such a revolutionary measure amid the setbacks for Union forces on the

fields of Virginia would take away much of the proclamation’s power, giving it

the appearance of a desperate move rather than a bold act. Lincoln agreed. He

held on to the document, waiting for a Union victory.

Lincoln later confessed to Secretary of

the Treasury Salmon Chase that at the start of the 1862 Maryland Campaign, he

made his decision on Emancipation. When Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of

Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River and began its invasion of Maryland,

Lincoln made “a solemn vow” that should Lee be stopped, he would “crown the

result by the declaration of freedom to the slaves.” While the fate of the nation

hung in the balance, and with the eyes of millions upon them, the Union Army of

the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia clashed near the

banks of Antietam Creek on September 17, 1862, in what was the bloodiest day in

American history. Two days later, Lee was gone from Maryland, and Lincoln had

his victory. He could now issue his proclamation.

On

January 1, 1863, after standing in line for hours to greet the customary New

Year’s Day visitors at the White House, Abraham Lincoln retired to his office

upstairs in the Executive Mansion. There he would fulfill his promises from

September and sign the final version of the Emancipation Proclamation. His

hands were tired and trembling from shaking so many hands, and as he prepared

to sign the document, as if to reinforce his resolve, he declared, “I never in

my life felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this

paper.” Lincoln affixed his signature to the Emancipation Proclamation, completing

what he would later call, “the great event of the nineteenth century.”

Emancipation

was indeed a great event. While it applied only to those states then in

rebellion, and thus left alone slaver in the Border States, it was still a

tremendous blow to slavery in the United States. It declared that from that

point on, the war would be fought to preserve the Union not as it once was, but

as it would and should be, one where all men and women would enjoy the

blessings of liberty.

The

Emancipation Proclamation was not a self-fulfilling document. It was an

important war measure, but only the first of many steps on the road towards

freedom for over four million slaves. More work still needed to be done to

secure its promise of freedom. Along with winning the war, a constitutional

solution to the problem of slavery was needed; that solution was eventually

found in the 13th Amendment. By 1865, slavery was abolished

throughout the country, and the union was not only restored, but rebuilt with a

“new birth of freedom.”

In

October of 1862, in reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation, Frederick

Douglass proclaimed, “We shout for joy that we live to record this righteous

decree.” Despite having some reservations about the proclamation’s

effectiveness, Douglass knew that history had been forever changed.

Emancipation meant, in the words of newspaper editor Horace Greeley, “the

beginning of the end of the rebellion; the beginning of the new life for the

nation.”

When

Lincoln first decided to issue the Emancipation Proclamation in July of 1862,

he knew that in order for its promise of freedom to become a reality, it would

require bloodshed and sacrifice on the battlefields of the Civil War. That is

what occurred at Antietam on September 17, 1862, giving Lincoln the opportunity

to issue his proclamation on September 22, 151 years ago today. The Battle of

Antietam and its relation to the Emancipation Proclamation is a stirring

reminder that throughout history, paper alone cannot secure freedom; only the

blood, sweat, and sacrifice of soldiers can make freedom a reality.

Sunday, September 8, 2013

Remembrance of the Fallen

Antietam National Battlefield

9/17/2012

Alann Schmidt

During the extensive planning for the

150th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, we tried to come up

with several different events to make the commemoration meaningful. At some point, I got the idea that it

would be a nice thing if we could have a ceremony and read the names of those

killed or mortally wounded in the battle.

Park management thought that it would be a good idea, especially when I

mentioned that we could make it an interactive event by having visitors

participate in the reading. I was

put in charge of the project, and among the many, many other things that we

were working on at the time (and believe me, there were many!) I started to put

together a list.

Originally I just had the names from

the rosters of identified Union burials in Antietam National Cemetery, and then

I added the rosters of identified Confederate burials from Washington

Confederate Cemetery in Hagerstown, Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Frederick, and

Elmwood Cemetery in Shepherdstown, WV.

This led to the quick realization that only a certain amount of soldiers

killed in the battle were buried in the area. In addition to the many buried as unknowns, there would have

been some taken home, some buried near hospitals, in private and church

cemeteries, and many other situations that would cause this list to be far from

complete.

I drafted a short notice to be posted

on our park website and Facebook site asking for help from the public, hoping

that if folks had knowledge and (hopefully) documentation on soldiers that were

killed or mortally wounded in the battle but for whatever reasonwere not buried

here we could also add those names to the list. I received responses from all over the country – from

Wisconsin, Louisiana, New York, Texas, South Carolina, Alabama, Indiana, Maine

- literally dozens of people emailed me with information, greatly enhancing our

list.

Thankfully, my notice also caught the

eye of Brian Downey, founder of Antietam on the Web. (aotw.org) Turns out he was also working on a

comprehensive database of soldiers killed at Antietam, and he graciously

offered to let me use his research for our list. This was a remarkable gesture, and helped considerably, for

now all I had to do is compare his list with mine and add them together to make

the master list for the event. He

even continually sent me updates as he found more information, and has the

ongoing list posted on the blog section of his website if you want to take a

look.

As time passed and the anniversary drew

closer, I started to get concerned since several visitors were very excited to

participate in the reading and contacted me wanting to be guaranteed the

opportunity to read their ancestor’s name. I still wasn’t quite sure how to carry out the public

participation part; we could just have a master list and have folks go up and read,

but what if someone didn’t want to stop (very likely) what then – would I have

to continually stand there to awkwardly move them along? Or what if everyone that showed up

wanted to read only names from Massachusetts for example, and I would have big problems

about who got to read what. Thankfully,

at some point I thought of separating the list into small sheets of ten to

twelve names and just giving each person a sheet to read. That way it kept things moving,

everyone got an opportunity, and you could still read as many times as you

wanted.

People still kept calling, nervous

about what time they should arrive to get their place in line, just exactly how

was this going to work, rightly skeptical when I just told them to show up,

we’ll make it work. Truth is, I

didn’t know if it was going to work, I had no idea how long it would take, how

visitors would react to the process, how smooth it would go, etc. etc. In the planning process for the entire

150th event it was necessary to come up with a schedule, and my

reading needed to fit that schedule.

When should it start? How

long will it take? I simply estimated

by guessing at the speed of how many names would likely be read per minute,

then per hour (by simply saying some out loud and timing it) and came up with

approximately 4 hours to get through the total of over 3400 names. The program was scheduled for 3 p.m.,

with hopes that it would be wrapping up near 7 p.m. By that time everything else for the day would be over, and

it would be just starting to get dark.

In addition, we planned a short closing ceremony for 7 p.m. to wrap up

the anniversary.

I had several other duties and programs

that weekend, and that anniversary day specifically, notably the very effective

“Voices from the Cornfield” program at dawn. I was still adding names to the list the night before the

event, and didn’t print out the final list (335 pages!) until the morning of

the 17th. I made two

copies of the list and placed them in big binders, one to hand out, and one for

me to follow along. As I arrived

at the cemetery, several visitors and hopeful participants were there early,

waiting on me. Ranger Isaac Foreman

and volunteer Frank Bell were there to help organize the line and pass out the

names, a huge help for me. I tried

to make sure everything was ready.

At three o’clock, a special ceremony

began the event. Rev. John Schildt

offered the invocation, Superintendent Susan Trail welcomed the crowd, the West

Virginia Air National Guard provided the colors, the U.S. Army Quintet provided

music, and nationally known and respected historian Ed Bearss offered comments

on the meaning of the event. As I

stood there distracted, all I could think about was if the time frame would fit,

whether the procedures would work, and how things would go. I think the world of Mr. Bearss, but as

I worried about the time, it seemed like his speech would go on forever.

Then, all the sudden, I stopped in my

tracks, as Ed told the crowd what a wonderful opportunity this was, to

recognize those lost, and that he wished he had an opportunity to recognize

those fighting beside him that died in WWII. He told about the incident when his team was ambushed on

January 2, 1944, leaving him severely wounded, and then he read aloud his

fallen comrades’ names. Wow! I suddenly stopped worrying and finally

realized what I was doing, what I was part of, what this means.

Susan, Ed, and a military honor guard then placed a wreath for all those buried as

unknowns, then I explained to the crowd how the reading would go. I asked those wanting to read to get in line to the left of the rostrum, get a sheet, and take their turn. We would read the names by state alphabetically, starting with Alabama. That instant, at least three dozen people got in line, and I don’t think it ever got much shorter than that throughout the event. Ed read the first sheet, then one by one visitors went through the line and read the names.

Isaac handed sheets out to the people in line, so they could familiarize themselves with pronunciations (I saw several practicing and asking for advice), or even trade with those looking for a specific name. At no time were there any disagreements, disruptions, or problems, everyone was so respectful. I stood at the top of the rostrum steps, directing folks to the podium and following along with the list. It was terrific meeting so many of the people that I had corresponded with before the event. So many were so appreciative, hugging me, thanking me - I can’t imagine a more fulfilling job or a more fulfilling day. Several folks made a special mention to the crowd, with pride, when it was their ancestor’s name they were reading.

I directed folks to leave by the other side of the rostrum, and most went around and through the line more than once; a couple of ladies went through more than ten times. It didn’t seem to matter where anyone’s particular allegiance was, they read for all states, respecting all that sacrificed. To simply keep the line flowing, I had folks just keep the sheets after they read, and I suddenly noticed something I hadn’t thought of. As I looked out across the cemetery I could see visitors walking with their sheets, finding the graves of the names they read. Talk about making a connection. I wonder how many left with the goal of finding out more about those soldiers. I thought to myself, maybe that’s the first time in 150 years anybody ever specifically visited some of those graves. Maybe it’s the first time since the roll call after the battle that someone even said some of those soldier’s names.

My good friend Ranger Dan Vermilya

often mentions his great-great-great grandfather Ellwood Rodebaugh, 106th

PA, in his battlefield presentations, as Private Rodebaugh was killed in action

in the West Woods. Dan hoped that

he would make it back to the cemetery to read Ellwood’s name, but wasn’t sure

when his hike would be finished. I

specifically kept the sheet with his name out of the stack, ready for Dan in

case he arrived in time. It looked

like he wasn’t going to get there, so I thought that I would read the sheet for

him. It wouldn’t be the same as if

it was Dan, but I hoped it would be good enough. Then, suddenly, at the last moment, in came Dan, and I

surprised him with the sheet. He

stepped up to the microphone, and added yet one more special element of this

amazing day.

As the sun slipped away, and more folks

gathered in the cemetery as the hikes were all completed, (and we were starting

on the Vermont section) I turned to Isaac and optimistically said, “I think we

are going to make it OK on time.” As

the last reader went past me and read the last names from Wisconsin, I stepped

to the podium and announced that the reading was complete and that we would

shortly begin our closing ceremony.

As I stepped away I looked at my watch and it said 6:56 p.m. Hopefully, to the visitors, it looked

like I had planned it that way, but I had no idea what actually was going to

happen, or how things possibly could have turned out so well.

For the closing ceremony I made a few prepared comments and then read the poem “Bivouacs of the Dead”. Our living history volunteers provided a 21 gun salute, played taps, and it was over. As I hugged the rangers that gathered around me, I was overwhelmed with emotion, and am still even now as I go over it again in my mind. This event, this commemoration, this memorial, was not about me, it is in every way about the fallen, but I am proud that I pushed for this, planned it, and carried it out, and that it turned out so well. I will never forget that day in the cemetery, for the rest of my career, for the rest of my life. Even though I have worked at Antietam for 12 years, this gave me a new perspective on the cost of this battle, and that each lost was not a statistic, but a specific person, and one that, on this day at least, was not forgotten. Ed Bearss said that this will be the next wave of battlefield special event, that in a few years every park will be reading names, following our example, just like so many places now do illuminations similar to ours. I sincerely hope so - for the attention it brings to that aspect of the battle stories, for those that get to participate in the readings, and especially for those who gave their all in service to their country - May they rest in peace.

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

Whiskey Courage in Abundance

“Whiskey Courage in Abundance”

K. Michael Gamble

As the Battle of Antietam raged

into a harvest of death, Confederate and Union soldiers were ordered to remain

steadfast in the execution of their orders. Evidence of their bravery was evident through out the day as

both armies attacked and counterattacked. As the toll of human life mounted, however, many soldiers

questioned the decisions that sent men into harms way. Were these orders given by officers who

were thinking in rational and logical ways, or were orders given by intoxicated

amateurs who were hell bent for glory at the expense of soldier lives? How prevalent was the use of liquor at

the battle, and did this affect the welfare of the troops?

.

The Irish Brigade had achieved a reputation

for its fighting spirit. These

Irish immigrants were proving that they were worthy of defending their adopted

country. During the attack on the

sunken road, Brigadier General Thomas F. Meagher ordered his troops in Brigade

formation over a cornfield, open pasture, and plowed field as well as three

fences towards an entrenched position supported by artillery. This frontal attack was ordered while

an adjacent brigade commanded by BG John Caldwell was flanking the Confederates

defenders to his left. In front of

the sunken road were troops from previous attacks protected by a small ridge 60

yards from the Confederates.

Troops from Nathan Kimball’s brigade were pouring rifle fire towards

Confederate brigades commanded by G.B. Anderson and Robert Rhodes as well as at

Richard Anderson’s reinforcements moving towards the lane from the south. In the middle of this intense fire

fight, BG Meagher was urging his men forward. Meagher will report that near the end of the engagement “My

horse having been shot under me as the engagement was about ending and from the

shock which I myself sustained, I was obliged to be carried off the

field”. Soon, rumors were

circulated that Meagher had been drunk and had actually fallen from his

horse. Colonel David H. Strother,

a member of General McClellan’s staff wrote in his diary the following day that

Meagher was not killed as reported, but drunk, and fell from his horse. Another story was circulated by

Whitelaw Reid of the Cincinnati Gazette that Meagher was “too drunk to keep the

saddle, fell from his horse …several times, was once assisted to remount by Gen

Kimball of Indiana, almost immediately fell off again”. These reports may have reflected

prejudiced viewpoints and the power of rumor and innuendo. However, there can be no doubt that Meagher

was a heavy drinker and had a lack of military knowledge and experience. For example, of the four regiments in

the Irish Brigade, only the 69th NY, 63rd NY and 88th

NY were ordered to charge the road after discharging five volleys. The 29th Mass had the most

protective position and was positioned between the 69th and 63rd.

As Meagher pointed out in his report, he sent orders only to the Irish commanders

and not to the 29th Mass.

Was there any advantage in holding the 29th Mass back? Was

this decision formulated with purpose or a spur of the moment reaction? What type of shock could have been

sustained that would entail evacuation from the field of action? One of Meagher’s regimental commanders, Colonel John Burke

disgraced himself by being conspicuously absent from his post as the 63rd

NY was being shot to pieces.

Many questions remain about Meagher’s actions and whether there could

have been a cover-up after the battle.

During the afternoon of the battle,

Major Thomas W. Hyde of the 7th Maine was ordered to take his

regiment across open ground south of the sunken road to clear confederate

sharpshooters from the Piper farm and orchard. The officer giving the order was the Sixth Corps Colonel

William Irwin. Hyde will claim

that only a drunkard would give such an order and suggested that it was a job

for a brigade not a regiment. Upon

Hyde’s request, Irwin repeated his order and the 7th Maine advanced

towards the Piper barn and haystacks where it was hit from three directions by

deadly rifle fire. Retreating back

to their jumping off point, the 7th Maine lost half of their 181 men. Hyde will later say that the order was

“from an inspiration of John Barleycorn in our brigade commander alone”.

Another example of “whiskey

courage” might have been MG James Longstreet himself. Suffering from a painful heel spur and a “crippled hand”

Longstreet was wearing a carpet slipper on his left foot during the

battle. As the Union army took

possession of the sunken road, they surged through the cornfield south of the

road and towards the Piper Orchard.

At this critical point of the battle, Longstreet held the reins of his

staff officers’ horses and ordered them to man firing positions among Millers

Battery which was on the perimeter of the orchard. LT William Owen described this situation as follows”

Longstreet was on horseback at our side, sitting side-saddle fashion, and

occasionally making some practical remark about the situation. He talked earnestly and gesticulated to

encourage us, as the men of the detachments began to fall around our guns, and

told us he would have given us a lift if he had not crippled his hand. But, crippled or not, we noticed that

he had strength enough left to carry his flask to his mouth, as probably

everybody else did on that terrible hot day, who had any supplies at command to

bring to a carry.” Straw papered liquor

flasks and a telescoping silver cup were popular accouterments in both the

Federal and Confederate Armies.

The ready source of liquor by officers was a source of much resentment

from the enlisted men.

Prior to the battle, Longstreet may

have shown self-discipline regarding drinking alcohol from a practical

perspective. While visiting his

new headquarters at the Piper home, Longstreet and D.H.Hill were offered

refreshments in the form of wine by members of the Piper Family. At first, Longstreet politely

declined. But after seeing General

Hill not experiencing any ill effects from drinking the wine, said “Ladies, I

will thank you for some of that wine”. (Too Afraid to Cry, p. 128)

The other Confederate wing

commander, Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, appeared more enamored

of fresh fruit than alcoholic beverages.

However, Major Henry Kyd Douglas, a member of Jackson’s staff, reported

that he observed Jackson taking a whiskey toddy on the march towards

Martinsburg Va (W.Va). Douglas

wrote “While mixing it leisurely, he remarked that he believed he liked the

taste of whisky and brandy more that any soldier in the army; that they were

more palatable to him than the most fragrant coffee, and for that reason he

rarely tasted them “(Battles and Leaders p. 623) Jackson could take his troops

to task about the presence of whiskey.

During one trip in the Potomac River, Jackson ordered staves of barrels

busted apart and dumped into the water.

Enterprising confederates went downstream with buckets and dipped the

diluted beverage for later use. Perhaps the dilution affected the taste. Commissary whiskey was described as

“bark juice, tar water, turpentine, brown sugar, lamp-oil and alcohol.”(p. 253

Billy Yank, Wiley)

Apparently, wine was a favorite

drink of the farmers as Mr. William Roulette who resided north of the Sunken

Road included “six gallons of blackberry wine @ $2 per gallon on his list of

compensatory items presented to the U.S. Government after the battle. This wine could have been used for

“medicinal” purposes since the Roulette farmhouse became the site of a field

hospital. Spirits were used for

medicinal purposes. Regiments had

a stock of “commissary” on hand as well as bottles of patient medicine that had

high alcohol content. (Soldiers Life, Time Life, 1996)

As the fighting reached its climax

at the Lower Bridge, Colonel Edward Ferrero was ordered to take the bridge at

about 12:15 PM. The attack plan

called for the 51st PA and 51st NY to conduct a direct

charge on the bridge from the bluffs east of the Antietam Creek with the 21st

Mass. in reserve. Standing in

front of the brigade before the attack, Ferrero shouted “It is General Burnside’s

special request that the two 51sts take that bridge. Will you do it?”

Apparently, the stillness was broken when Corporal Lewis Patterson yelled

towards the Colonel “Will you give us our whiskey if we take it?” Ferraro’s reply was “Yes by God, you

shall all have as much as you want, if you take the bridge. I don’t mean the

whole brigade, but you two regiments shall have just as much as you want, if it

is in the commissary or I have to send to New York to get it, and pay for it

out of my own private purse, that is if I live to see you through it! Will you

take?” “Yes” was the resounding

answer. On September 19, 1862,

Colonel Edward Ferraro was promoted to Brigadier General and on the next day,

the 51st Pa got their whiskey as promised.” (Will you give us our

whiskey” p...22 Civil War Battles Brother vs. Brother Special Issue Summer 2006)

Perhaps General McClellan was not aware of Ferraro’s promise. McClellan was on record for condemning

the use of liquor amongst his troops. After liquor provoked insubordination in

Hookers Division in February, 1862, McClellan stated the following “No one evil

agent so much obstructs the army…as the degrading vice of drunkenness. It is the cause of by far the greater

part of the disorders which are examined by courts martial. It is impossible to estimate the

benefits that would accrue to the service from the adoption of a resolution on

the part of officers to set the example of total abstinence from intoxicating

liquors. It would be worth 50,000

men to the armies of the United States.” (Hqrs. Army of Potomac G.O. 40.

February 4, 1862)

After the Battle of Antietam, the

disagreeable task of burying bodies left out in the elements for four days fell

to the 137th Pennsylvania Regiment. An officer named Bingham secured permission from the provost

marshal’s office to buy liquor for his men because he believed they would be

able to carry out their orders only if they were drunk. (The Republic of

Suffering P. 69).

The evidence is conclusive. Liquor was used by soldiers during the

Battle of Antietam. At times,

officers in positions of authority had been drinking liquor. Did this drinking affect the final

outcome of the battle? It appears as that it was more the absence of well co-coordinated

and cohesive planning and the large numbers of inexperienced soldiers that had

the most impact. The horrors of

combat affected the soldiers in many ways and the acceptance of liquor in the

19th century as a panacea for all problems is evident. It is understandable that the military

reflected the values of American society

and that the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest one day in American

history, produced enough horror and devastation to be tempted with some induced

relief from liquor.

Monday, May 20, 2013

FDR Visits the Battlefield

A Presidential Visit by Ranger Mike Gamble

Seventy-fifth

Anniversary of the Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1937

The Last Great

Reunion at Antietam

Memories of what it was like during

the Battle of Antietam at Sharpsburg Maryland were still vivid to some of the

participants who gathered for this historic reunion in 1937. Approximately fifty Civil War

veterans and a crowd of thirty-five thousand gathered at the battlefield to

hear the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, give a stirring speech and to view a

re-enactment of the battle. From

the grandstand erected overlooking the famous Bloody Lane, visitors were able

to view one thousand National Guardsmen simulate combat. Units came from Maryland, Pennsylvania,

the District of Columbia, as well as active army soldiers from Fort Belvoir,

Virginia. Major General Milton A. Reckord, Commander of the Twenty-ninth

Division was overall commander of the program. Union solders were dressed in barrack caps, O.D.

shirts and blue denim; Confederates appeared in campaign hats and khaki. Action started with the "Confederates" waiting in

the road for the "Union" attack. Upon being attacked, the "Confederates" retreated and then counterattacked. The narrator, Major Joseph W. Byron, Retired, described the

action which in turn was broadcasted on a local radio station in Hagerstown.

Major Byron planned the entire military program for the Antietam Celebration

Commission. The Commission was

represented by Senators Tydings and Radcliffe of Maryland, Senator Harry Flood

Byrd, of Virginia, Representative David J. Lewis of Maryland, and

Representative Charles A. Plumly of Vermont.

Regular Army engineers simulated

the noise of battle. Smoke bombs

burst in the sky, and two wooden farm buildings erected on the battlefield were

put on fire and burned to the ground.

One interesting scene was a replica of a wooden Confederate battery that

blew up from a charge of explosive planted underneath it as though it had been

struck by a Union shell.

Colonel John Oehmann, District Building Inspector and Head of

the District of Columbia National Guard portrayed General Robert E. Lee. Colonel John D. Markey of Frederick

Maryland, Commander of the 1st Maryland Regiment, portrayed General George B. McClellan. Twenty-two spectators were treated for

injuries; most of whom had fainted from fatigue or perhaps from

excitement. They were treated by

the 104th Medical Regiment of Baltimore.

Following the battle, the assembled

crowd stood for the playing of the National Anthem as Boy Scouts marched in

front of the grandstand with the

flags of 30 states representing

the homes of the soldiers who were in the battle. The President received a memento of the fighting; a

brightly polished wood with a bullet imbedded in it chopped from a tree near

Burnside's Bridge.

Civil War veterans from Maryland and Pennsylvania in attendance

included George Leighty, from Hancock, Maryland, one of two remaining

veterans of Washington County.

He served with the 3rd

Regiment, Maryland Infantry.

Other area veterans in attendance were F.L. Mullinix from Westminster, Maryland who served with 7th

Maryland Regiment, and Edward Flickinger, Dry Run, Pennsylvania from the 11th Pennsylvania Regiment. Flickinger was the last survivor of the Civil War from

Franklin County.

` The day before the program, September

16, twenty-one veterans toured the battlefield and observed that the corn was

"more mature" than what they remembered seventy-five years ago. Veterans were also part of a special

dinner held in their honor at the Hotel Alexander Ballroom in Hagerstown,

Maryland. Twenty-four veterans,

the Governors of two states and representatives of governors were guests.

In addition to the program on

September 17, a huge

exposition had been held at the Washington County Fairgrounds beginning on

September 4. "On the Wings of

Time" was a pageant that

featured a cast of two thousand.

Episodes of history over the past 200 years were depicted twice a

night. The oldest and the newest

railway equipment were brought in on a special spur of track. Airplane and blimp demonstrations

appeared overhead. An estimated sixty thousand spectators viewed the pageant

during its fourteen-day run.

All of the programs were well

publicized through the Associated Press Wire Service and people from throughout

the United States became aware of the rich historical heritage found in the

surrounding tri-state area. Coming

on the heels of the great depression, it is worthy to note the pride that

residents had in celebrating these historical events.

President Roosevelt closed his

speech that day with words that placed focus on the importance of a united

country. His words bear wisdom

today as they did in 1937. He stated "In the presence of the spirits of

those who fell on this field--Union soldiers and Confederate soldiers--we can

believe that they rejoice with us in the unity of understanding which is so

increasingly ours today. They urge

us on in all we do to foster that unity in the spirit of tolerance, of

willingness to help our neighbor, and of faith in the destiny of the United

States.”

Sunday, May 19, 2013

The Early History of the Battlefield by Brian Baracz

Early History of the Antietam Battlefield

On

September 17, 1862 Union and Confederate forces clashed in and around the

peaceful town of Sharpsburg, Maryland.

When the battle was over, more than 23,000 men were strewn across the

pastoral fields killed or wounded in what was, and still is today, the single

bloodiest day in the history of the United States. Today, the park shows few signs of this terrible clash of

men during the Civil War, only woodlots, cornfields, and an occasional home and

bank barn dot the landscape.[1] It is a place of peace and tranquility,

a place for reflection. Through

the early, significant work of the Antietam Battlefield Board, many reunions

and monument dedications, and the recorded

memories of veterans that took part in this watershed of American history,

the Antietam National Battlefield is one of the best preserved battlefields in

the country.

When

the plan to preserve America’s Civil War Battlefields was initiated in the

1870’s the country was still very young, not even 100 years old. Many people had grandfathers who had

fought during the Revolution.

Millions of others were witness to or had a connection with the Civil

War and they believed it was their duty or obligation to preserve these sacred

battlefields.[2] The establishment of national military

parks began in 1890 and initially four battlefields were chosen to act as a

Battlefield Park System. Each site

chosen was designated to remember a specific army. For example, Gettysburg was chosen to memorialize the Union

Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia; Chickamauga

remembered the Union Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of

Tennessee; and Shiloh honored the Union Armies of the Tennessee and Ohio and

the Confederate Army of the Mississippi.

After further discussion, it was deemed proper to also remember the

Union Army of the Tennessee at Vicksburg because that was thought to be that

army’s most successful operation.[3] Antietam Battlefield was not one of the

parks chosen to be included in the Battlefield Park System, but it was still deemed

important enough that preservation efforts started in 1890.

There

were two laws passed in Congress in 1890 that provided the legal basis for the

Antietam National Battlefield.

Today, relatively little is known about either of these laws except for

the fact that they provided money for maintaining the National Cemetery,

improving the grounds around the National Cemetery, and “for the purpose of

surveying, locating and preserving the lines of battle.”[4] The first step for locating the

lines of battle came on August 1, 1891 when the Secretary of War appointed

Colonel John C. Stearns, who served in the Union Army, and Major General Henry

Heth, from the Confederate Army, as the men who formed the Antietam Board.

When

the Antietam Board was organized, one man was highly recommended to be placed

on the Board, but he was overlooked.

His name was Ezra Carman, and he served as Colonel of the 13th

New Jersey Volunteers at the Battle of Antietam. He was wounded during the war at the Battle of Williamsburg

in 1862 and lost almost all of the use of his right arm and during the fight at

Kenesaw Mountain, Georgia in 1864 suffered almost a complete loss of

hearing. Despite these physical setbacks,

his military career was capped by being brevetted Brigadier General in 1867.[5]

When

he was informed of a new opening on the Board he made another attempt to become

a member and was not overlooked a second time. On October 8, 1894, Ezra Carman was appointed to the

position of “historical expert.”[6] At the same time he was added to the

Board, two new positions were created.

Former Union General George B. Davis was named the first President of

the Antietam Battlefield Board.

Jedediah Hotchkiss, former Confederate mapmaker for General Thomas ‘Stonewall’

Jackson, was selected as mapmaker for the Antietam project.[7]

The

Antietam Board sought to contact veterans asking for their reminiscences of the

great battle. This process was

already underway because of the formation of the various veterans groups during

this time period. In addition to

receiving much information from these groups, ads were placed in newspapers

announcing the work of the Board and their request for information from

veterans regarding the battle.

Once a veteran contacted the Board it was not uncommon for numerous

letters to be sent between the two parties and for the veteran to send back, in

addition to their written memoirs, a map provided by the Board asking the old

soldier to mark the map with the position held by their regiment during the day

of battle.[8] The amount of information that flowed

into the Antietam Battlefield Board’s office enabled the men the opportunity to

cross reference information regarding battle specifics from numerous sources,

thus providing the most accurate tactical study of the battle.

It

would seem with Hotchkiss enlisted to draw the map of the Antietam Battlefield

that this job of the Board would have been completed with little effort, but

that is quite the contrary. When

Hotchkiss received his letter of appointment, he was informed he would only

have sixty days to complete his task.

Because of numerous problems and setbacks, the map was not completed in

the allotted amount of time and Jedediah Hotchkiss was let go in April 1895

from the Antietam Battlefield Board.

It was at this point, they were left to go about collecting veteran’s

recollections with only the crude maps created by Stearns and Heth during their

few years together. [9]

An

important accomplishment of the Antietam Board was the eventual completion of a

map of the Antietam Battlefield.

(It is important to note at this time that during the late summer of

1895 a new President of the Antietam Battlefield Board was named, George W.

Davis. The first President

Davis had been promoted and transferred to the United States Military Academy

in West Point, New York.)[10] In May of 1897, President George W.

Davis requested help from the Gettysburg Battlefield Commission, “in connection

with the preparation of a Map of the Antietam Battlefield.”[11] Col. Emmor Bradley Cope, Hays W. Mattern, Edgar M. Hewitt and

John E. Cope began their work at Antietam and as it turned out Mattern and

Hewitt did most of the work on the Antietam map. Because of the proximity of Gettysburg to Antietam, Col.

Cope was not at Antietam on a regular basis; he remained at Gettysburg and just

offered suggestions to Mattern and Hewitt in their preparations of the map.

With

the completion of the base map, (known today as the Carman-Cope Map) it was

time to add all the information from the Official Reports, unit histories, and

veteran’s correspondences to the map to provide a minute-by-minute history of

the battle. Due to the passing of

Heth in 1899, Carman became the foremost authority in the implementation of

this task. The project was

initially going to be nine maps, with six of the nine showing the various

positions regiments held throughout battle. When the Antietam maps were completed in 1904 there

ended up being fourteen maps with the final artwork done by a man named Charles

H. Ourand.[12]

The final report

of the Antietam Board was submitted by President George W. Davis on March 18,

1898. The cost for the salaries of

the civilian board members, surveys and maps, land, roads and fencing, observation

tower, tablets and other various markers

(monuments to the six generals who were killed or mortally wounded

during the battle), and finally other miscellaneous costs totaled $74,081.69.[13] (It should be noted that no actual land

was acquired, just right-of-way access on the roads.) Over the next forty years, that there were no major

improvements or federally funded undertakings at Antietam. The one exception came in 1904 when

Ezra Carman was allowed to make a few corrections and additions to the tablets

for a nominal cost.[14] The early work of acquiring the lands

around the Antietam Battlefield and establishing it as

one of the most significant battlefields of the Civil War can be attributed to

the actions of a few individuals and the memories of the thousands of veterans

who corresponded with the Antietam Battlefield Board, specifically Ezra Carman.[15]

The transfer of

Antietam and other “historical areas” from the War Department to the National

Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior took place on August 10,

1933 by order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[16] From that day forward, it has been the

mission of the NPS to continue the work started the War Department over

one-hundred years ago. Today the

Nation Park Service strives to preserve, protect, interpret, and improve for

the benefit of the public the numerous resources associated with the Battle of

Antietam and it legacy.

[1]

Bank barns are the style of barn most typically found in this region of Maryland. The barn has an upper and lower

entrance to make it easier for a farmer to store their crop in the upper

section and drop feed to their animals in the lower area. These barns are also distinctive

because of the ‘cuts’ or ‘slits’ in the side stonework. The cuts are needed because when

‘curing’ green hay, enough heat can be produced that spontaneous combustion

could occur and burn the barn to the ground. The cuts provide ventilation to prevent this from happening.

For more information on historic barns see, Michael J. Auer, The Preservation of Historic Barns, [on-line

book] available at http://www2.cr.nps.gov/tps/briefs/brief20.htm.

Last accessed November 3, 2003.

[2]

Ronald F Lee, The Origin and Evolution of the National Military Park Idea

(Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior: National Park Service, 1973)

2.

[3]

Lee, Military Park Idea, 24.

[4]

Snell and Brown, ANB & NC: History,

69.

[5]

David A. Lilley, "The Antietam Battlefield Board and Its Atlas: or The

Genesis of the Carman-Cope Maps." Lincoln Herald 82, no. 2 (1980):

382.

[6]

Snell and Brown, ANB and NC: History,

84-85.

[7]

Lilley, ABB and Its Atlas, p.382. Davis was the president of the board on

the publication for the Official Records and through this project became

familiar with Hotchkiss’s work and expertise thus bringing him onboard for this

project.

[8]

Lilley, ABB and Its Atlas, 383.

[9]

In his article on the Carman-Cope maps, Lilley wrote, “In justice to Hotchkiss

it is also important to observe that Col. Emmor Cope first estimated that

Antietam could be mapped in three months; more than five times that period

elapsed before the job was completed, a revealing footnote to compare with the

time originally allotted Hotchkiss.” Lilley, ABB and Its Atlas, 384.

[10]

Davis wrote in regards to his being at West Point, “I am at too great a

distance to direct the work to advantage.” Snell and Brown, ANB and NC: History, 101.

[11]

Snell and Brown, ANB and NC: History, 106.

[12]

Lilley, ABB and Its Atlas, 385.

[13]

Snell and Brown, ANB and NC: History,

108.

[14]

Snell and Brown, ANB and NC: History,

113.

[15]

The wealth of information and material collected by the Antietam Battlefield

Board can be located at: 1. National Archives Record Group No.92, Office of the

Quartermaster General, Entry 705- Correspondence and maps of the Antietam

Battlefield Site Board, 1893-1894. 2.National Archives Record Group 94, Records

o the Adjutant General’s Office, The general Ezra A. Carman Papers, three or

four boxes of correspondence 1895-1897, consisting of letters sent and received

by Carman regarding troop positions at Antietam. 3. Manuscript Division,

Library of Congress, Ezra A. Carman Papers, in eight boxes. Seven contain an unpublished manuscript

“History of the Maryland Campaign” and one box has notes and maps for this

unpublished work.

[16]

The transfer of forty-eight properties included eleven national military parks,

two national parks, ten battlefield sites, ten national monuments, four

miscellaneous memorials, and eleven national cemeteries. Snell and Brown, ANB and NC: History, 146.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)